I. Introduction

Escada. Once a force in 1980s fashion, known for bold silhouettes and saturated colour, the brand today is more likely found in duty-free aisles than on high-fashion runways. While its fragrance line, licensed to Coty, has endured through a series of crowd-pleasing, accessibly priced perfumes, Escada’s ready-to-wear collections have faced a prolonged struggle for relevance. Over the years, Escada has undergone major ownership shifts and creative resets, with renewed efforts underway to reposition it for today’s consumer.

This case study examines the structural issues that led to Escada’s decline - from missed aesthetic shifts to brand dilution through licensing, while assessing its current revival strategy. By understanding both the brand’s legacy and its reinvention attempts, we explore whether Escada can still carve out space in a crowded and fast-evolving luxury market.

II. From Munich to Madison Avenue: Escada’s Ascent

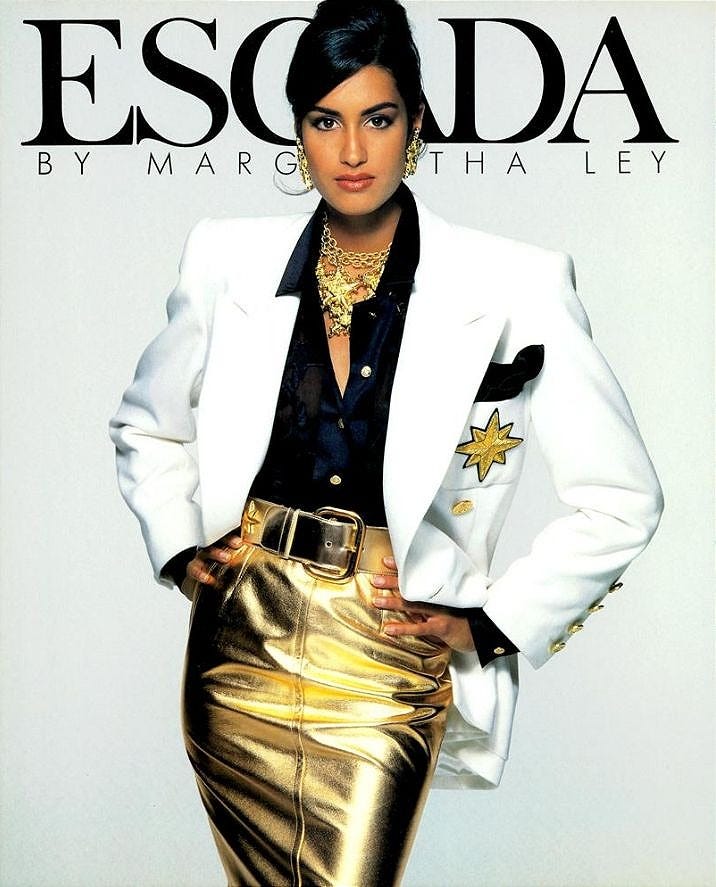

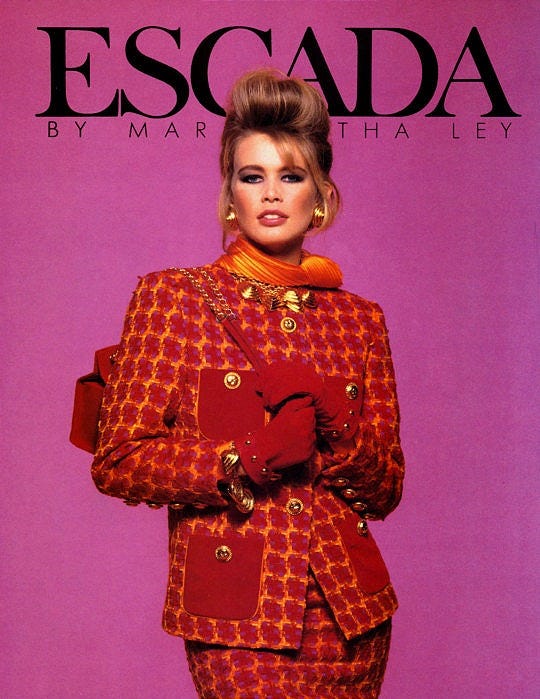

Founded in 1978 by Margaretha and Wolfgang Ley, Escada entered the luxury fashion space with a clear proposition: couture-level craftsmanship infused with high-voltage femininity. Margaretha, a former Dior model and trained seamstress, brought a rare blend of technical skill and creative vision to the brand. Escada quickly became known for its colour-rich, highly decorated sportswear, offering an alternative to the restrained minimalism dominating European runways.

By the early 1990s, Escada had evolved into a global powerhouse with over $800 million in annual sales. The brand’s growth was meteoric. Escada went public in 1986, with the Leys retaining majority voting control. It expanded across 1,200 retail points and operated 140 boutiques worldwide, including a six-story flagship on New York’s 57th Street. Escada also diversified its portfolio, producing additional labels like Crisca, Laurel, Apriori and Natalie Acatrini, and held stakes in brands such as St. John Knits and Badgley Mischka.

Margaretha Ley’s aesthetic vibrant colours, bold prints, and precise tailoring perfectly aligned with the aspirational energy of the 1980s and early ’90s. The brand offered a polished uniform for ambitious women, blending glamour with gravitas. Her passing in 1992 marked the beginning of a creative vacuum the brand would struggle to fill.

III. Economic headwinds and aesthetic drift

The late 1990s and early 2000s ushered in a new aesthetic era, with a mix ranging from Tommy Hilfiger’s preppy Americana and Calvin Klein’s minimalist chic to Ralph Lauren’s classic sophistication, which is often referenced as a precursor to today’s quiet luxury trend. At the same time, Y2K fashion introduced an ultra-casual, youth-driven sensibility that dominated pop culture.

These shifts weren’t purely stylistic. Economic factors also played a role. The early 1990s recession and the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2001 pushed consumers toward more understated fashion. In an era of financial caution, minimalism became the dominant language of luxury: stealth, not sparkle, signalled status.

Escada, however, stayed the course. It remained committed to its signature codes: vibrant colours, bold prints, boxy cuts, and decorative embellishments. What once felt confident and commanding began to feel dated and out of step. There was no creative overhaul or fresh design voice to reinterpret the brand’s DNA for a new generation.

As fashion sensibilities evolved, Escada’s core clientele aged. Gen X and millennial consumers, drawn to authenticity, subtlety and modern storytelling, found little to connect with in the brand’s unapologetically glitzy aesthetic. The loss of Margaretha Ley in 1992 further deepened the gap. Without its founding creative force, Escada struggled to evolve. What had once captured a cultural moment was now losing its footing.

IV. Licensing, losses and the limits of nostalgia

As Escada’s ready-to-wear collections lost relevance, its fragrance business quietly became the brand’s financial anchor. Licensing agreements with Procter & Gamble and later Coty helped establish Escada as a major player in the fragrance category, thanks in part to its now-standard model of limited-edition summer scents. These crowd-pleasing, accessibly priced perfumes kept the brand visible, but also contributed to a shift in consumer perception. Escada became better known for its scent than its style. When a fragrance line outpaces the runway, identity blurs, and fashion credibility begins to erode.

Meanwhile, the business behind the brand faltered. In 2009, Escada filed for bankruptcy after years of declining sales and strategic drift. It was acquired by Megha Mittal, who sought to reposition the label with new product lines and celebrity campaigns, including a high-profile collaboration with Rita Ora. The revitalisation efforts brought temporary visibility but lacked staying power. By 2019, Escada was again in trouble. A second bankruptcy followed in 2020, now under the ownership of private equity firm Regent, L.P. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the brand’s challenges, and in 2022, Escada America LLC filed for Chapter 11 protection.

Repeated financial distress reflected more than macroeconomic headwinds. Escada’s core challenges were structural—an unclear brand identity, missed generational shifts, and an over-reliance on past formulas that no longer resonated.

V. Learning from the survivors: what Escada missed

Several luxury brands have managed successful repositionings over the past two decades by combining strategic clarity with strong creative leadership. Gucci under Tom Ford set the tone in the late 1990s with a sharper, more modern aesthetic. Burberry, under Christopher Bailey, overcame early 2000s brand fatigue by focusing on digital innovation, product consistency and a renewed sense of British identity. Both transformations were anchored by clear design direction, targeted investment in core categories, and strong executive alignment.

Escada, by contrast, lacked that consistency. Since 2009, the brand has undergone multiple changes in leadership and creative direction, including stints by Jonathan Saunders, Niall Sloan and Emma Cook. While each designer brought different strengths, the transitions were frequent, and the collections did not build enough momentum to reposition the brand in a meaningful way.

Attempts to modernise the product offering also fell short. Escada continued to focus on ready-to-wear while underinvesting in key luxury categories such as leather goods. Accessories, particularly handbags, can account for up to 90 percent of revenue at leading fashion houses. While Escada made moves in this area, including a collaboration with Rita Ora on the Heart Bag, these initiatives lacked follow-through and scale.

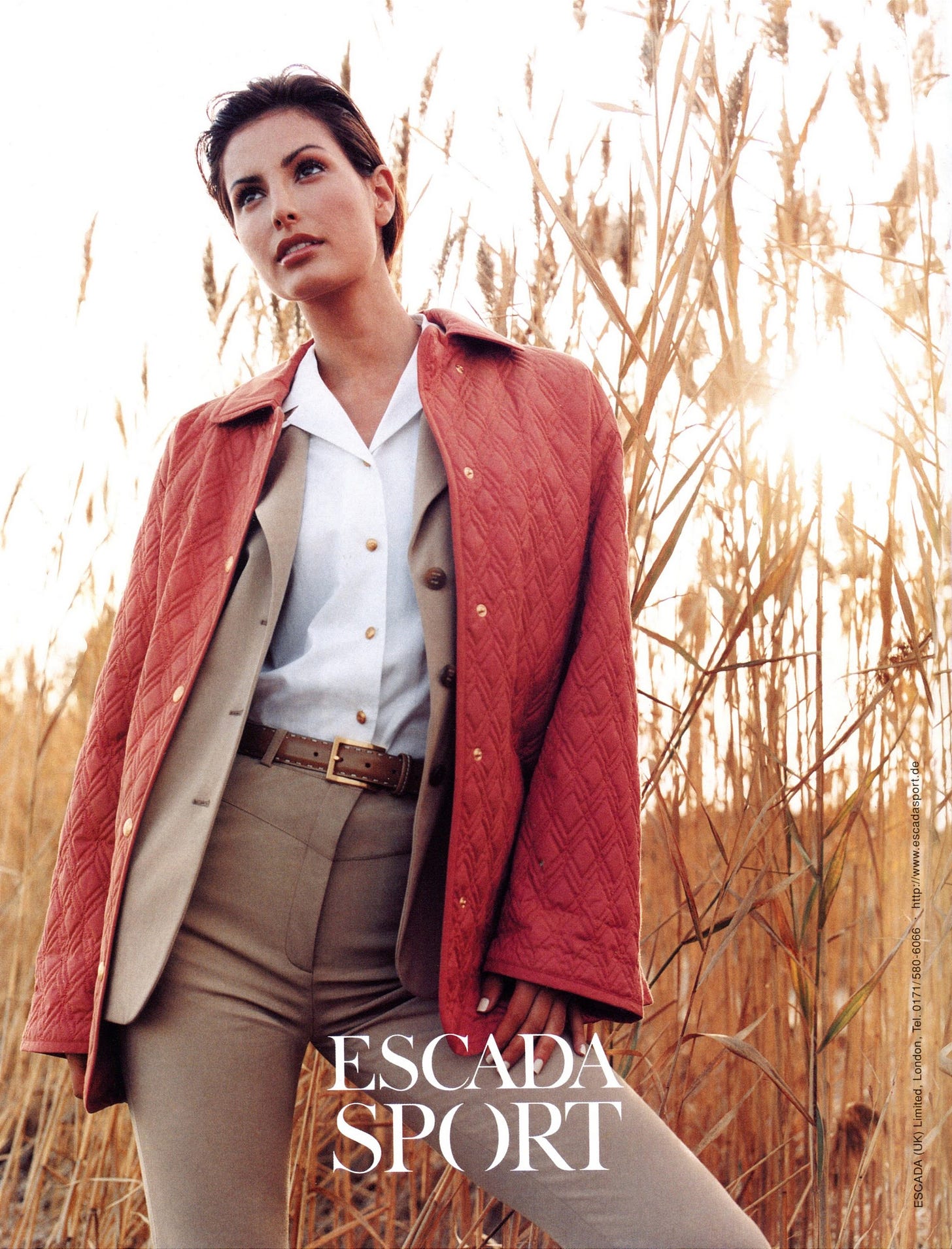

The brand did explore broader appeal through Escada Sport, a more accessible diffusion line launched in the 1996s. Positioned to offer casual daywear and lower entry price points, the line initially gained traction, particularly in the UK and Germany. However, inconsistent creative direction and limited global visibility meant that Escada Sport struggled to become a meaningful engine of growth or recruitment tool for younger consumers.

VII. So, what comes after nostalgia? Escada’s next test

Escada has taken steps toward regaining relevance, including launching new campaigns and expanding into categories like jewellery and watches. Creative direction is now led by Ioana de Vilmorin, whose background includes work with Christian Lacroix and Isabel Marant. Her appointment reflects an intent to refine Escada’s aesthetic and re-establish credibility in luxury fashion. But movement alone is not momentum.

Escada remains caught between tiers. The brand is priced to compete with luxury peers, yet lacks the product distinction, consistent creative identity, or cultural relevance to justify that position. It is not niche enough to build community, and not elevated enough to anchor prestige.

As Luca Solca of Bernstein notes, the digital age favours either scaled mega-brands or tightly defined niche players. Brands in the middle face the most pressure, and Escada currently sits in that exposed space.

Its past celebrity strategy highlights the gap. Collaborating with Rita Ora brought visibility but misaligned the brand with a more mass-market image. By contrast, brands like Genny, a 1960s-era Italian label, has been quietly regaining relevance through red carpet placements and carefully chosen fashion ambassadors to create renewed buzz and maintain aspirational value.

For Escada to move forward, several strategic shifts are essential:

Partner with culturally relevant, high-fashion ambassadors who can elevate brand perception.

Refine product design to reflect current luxury expectations. Keep boldness, but update it with tailored construction, premium materials, and sharper silhouettes.

Engage in high-visibility moments. Fashion weeks, global art events, and capsule launches can generate traction and help reposition the brand with authority.

Activate the archive: Tap into the archival dressing trend with curated reissues and red carpet placements of vintage pieces. Stylists like Law Roach have shown how vintage can drive relevance and visibility.

Make a definitive market choice. Either own a niche with clarity or reinvest in becoming a true luxury player. Straddling both will not deliver traction.

Escada’s legacy may open doors, but the future depends on focus, taste, and strategic execution. The next phase cannot rely on name recognition alone.